I read my first Jonathan Carroll novel shortly after discovering Graham Joyce. I’d read everything Joyce had written up to that point and was desperate for more. The top recommendation I kept hearing at that time was Jonathan Carroll, probably because there’s a certain similarity between the two writers: they both write fiction set in our contemporary reality with relatively small added fantasy elements. You can call this magical realism, but Joyce disagrees with this classification—he prefers the wonderful term “Old Peculiar” to describe his fiction—and I’m not sure if Jonathan Carroll is completely happy with it either. Still, it does seem to fit the bill somewhat and provides a good point of reference for people who are unfamiliar with them.

While there may be touching points with magical realism in both authors’ works, there are also considerable differences between them in terms of style and tone, so it’s a bit of an oversimplification to constantly call out their names in the same breath. Still, I think that many people who enjoy one of these excellent authors’ works will also enjoy the other one.

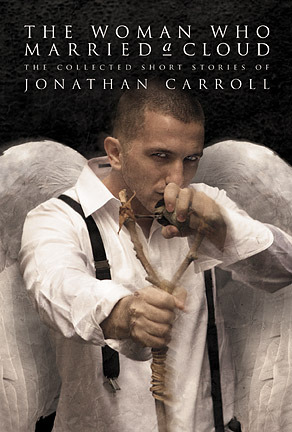

All of this serves to say that, if you’ve just read Graham Joyce’s wonderful new novel Some Kind of Fairy Tale (check out Niall Alexander’s wonderful review here) and, like me, you’re now somewhat grouchy about having to wait a year or more for his next one, here’s the perfect opportunity to discover Jonathan Carroll’s works: the new, huge, career-spanning short story collection The Woman Who Married a Cloud, out on July 31st from Subterranean Press.

Jonathan Carroll is best known for his novels, but has also produced an impressive body of short fiction over the years. There’s a certain pattern to the way Carroll sets up the lives of the (mostly) regular people who inhabit his novels and then gently whacks them out of their expected paths by introducing something magical and transcendent. “Pattern” isn’t meant to be a negative, here. It’s somehow still frequently surprising, and always beautiful and meaningful. As Neil Gaiman wrote in the introduction for Carroll’s website: “He’ll lend you his eyes; and you will never see the world in quite the same way ever again.”

In terms of themes and style, Carroll’s short stories are similar to his novels. The main difference is obviously a function of the difference in length: while it usually takes his novels a while to build up, the short stories go from common to cosmic surprisingly quickly. Expect a great many short stories that introduce a thoughtful, interesting protagonist whose life at some point suddenly intersects with (to use this word again) the transcendent: he or she discovers something about the true nature of the human soul, or love, or reality, or God.

Sometimes these stories introduce their magical elements early on, allowing the author to explore their profound effects on his characters in some depth. Occasionally the stories end at the exact moment of revelation, creating one of those reading experiences where you just have to close the book for a moment to let everything sink in. This leads me to maybe the most important suggestion I can make, if you’re planning to read this book: sip, don’t binge. One or two stories per day. Allow them some time and space to breathe and expand. Savor the delicacy of Carroll’s prose:

From the beginning, he wanted no pity. Wanted no part of the awful, gentle kindness people automatically extend when they discover you are dying. He had felt it himself years before for his mother when the same disease slowly stole her face; all of the ridges and curves of a lifetime pulled back until only the faithful bones of her skull remained to remind the family of what she would soon look like forever.

Because he liked the sky at night, the only thing “cancer” originally meant to him was a splash of stars shaped vaguely like a crab. But he discovered the disease was not a scuttling, hard-shelled thing with pincers. If anything, it was a slow mauve wave that had washed the furthest shores of his body and then lazily retreated. It had its tides and they became almost predictable.

I realize that’s a long quote to include in a review, but please realize that the following few dozen paragraphs (from the start of “The Fall Collection”) are just as tender, sad and gripping. Where to stop? Not all of the writing in this collection is this powerful—but much of it is. Jonathan Carroll is a master at portraying “the sadness of detail,” and just like the artist in the eponymous story, that is what makes him “capable of transcendence.” I found myself going back and rereading passages over and over again.

The Woman Who Married a Cloud contains a few novella-length works and a few short, stunningly intense vignettes that convey a short, simple, powerful image, but the vast majority of the stories fall in the middle range of ten to twenty pages: just enough space to introduce and develop one or two fascinating characters and then show and explore the moment when their perception of reality changes forever.

For some reason, I’d only read one of the 37 (!) stories included in this collection before, so this book was a bit of a revelation for me. If you like Jonathan Carroll’s particular brand of magic, you now have the opportunity to get a large number of bite-sized bits of it in one volume. I can’t think of a better way to discover this amazing author.

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. His website is Far Beyond Reality.